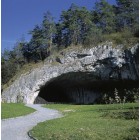

The Moravian Karst

is the largest and most highly developed karst area, with the widest range of karst phenomena, in the Czech Republic. Every kind of karst formation with the exception of polje – enclosed karst depressions – can be found here.

The Macocha Abyss

is 138.5 metres deep and is the largest gorge of its kind in the Czech Republic and Central Europe. The upper part (or mouth) of the gorge is 174 metres long and 76 metres wide. The River Punkva, which feeds two lakes, flows along the bottom of the gorge. The upper lake is approximately 13 metres deep and can be seen from above. The lower lake is hidden among the rocks and is not visible from above. It is more than 49 metres deep. Its bottom has yet to be reached.

The first man

known to have descended to the bottom of Macocha was the monk Lazar Schopper from Brno, later Prior Provincial of the Minorite order in Moravia – he achieved the feat in 1723.

The cableway

connecting the Punkva Caves with Macocha is 249 metres long (with a horizontal length of 207 metres) and spans an elevation of 131 metres, making it the steepest cableway in the country. It connects two points – the Punkva Caves (362 metres above sea level) and Macocha (493 metres). The transport speed of the cableway is 2.5 m/s. Its two cabins hold 15 people and the journey time amounts to less than three minutes.

The Rudice Sink

is, at 153 metres, the deepest dry gorge in the Czech Republic. It is located in the Rudice Sink – Býčí Skála cave system. The gorge was discovered by speleologists climbing the U Kašny stack right above the active riverbed of the Jedovnice Stream. Ascents to a height of 146 metres proved possible in time. Following accurate measurement and the digging out of a seven-metre plug, a new entrance was built on the surface which can be found on the edge of the forest to the south of Rudice.

The Amateur Caves

in the Moravian Karst is the longest cave system in the Czech Republic. The areas explored to date amount to a length of almost 35 km.

The first automobile

in the country was made in Adamov in 1888–1889 just three years after Daimler’s first automobile with a combustion engine. Only one “Marcus” automobile with a four-stroke petrol engine was, unfortunately, made. Today, it is the pride and joy of the Technical Museum in Vienna.

Mysterious skulls

were discovered in 1991 in the charnel house beneath the church in Křtiny. Among the skeletal remains of around a thousand people, twelve skulls were discovered that were painted with black laurel wreaths and the Old Canaanite letter Tau. These skulls, whose strange ornamentation evidently dates back to the seventeenth century, may have belonged to distinguished persons – members of the religious order, though a bold theory has emerged according to which they are the skulls of some of the twenty-seven Czech lords executed in 1621. Whatever the truth may be, a number of them can now be seen in the newly restored charnel house in Křtiny.

The oldest cave painting

in the Czech Republic is found in the Býčí Skála (Bull Rock) Cave in the Josefov Valley. The cave is famous primarily for the archaeological discovery of an extraordinarily large burial site from the Early Iron Age and the finding of a statue of a bronze bull. The prehistoric painting is found in an inaccessible part of the cave. Its story is described by archaeologist Mgr. Martin Golec, Ph.D.:

“Býčí Skála has ceilings in the Old Býčí Skála that have been accessible since time immemorial and discoloured by the torches of its visitors. The walls are covered with the signatures of hundreds of inquisitive people who have sought contact here with a mysterious world, an enlightened ideal in the womb of nature or a romantic excursion to the underground. The painting is found in a small recess at the end of the large amphitheatre known as the South Branch in Old Býčí Skála. It does not belong to the Palaeolithic, as we might expect. The site was an extensive winter camp for the Magdalenian hunters for millennia. It is younger, belonging to the Eneolithic, and we can date it back approximately to the middle of the fourth millennium before Christ. How did it escape detection from so many eyes? It is a geometrical structure of hatched triangles and lattices, in the fashion of the times. Nothing realistic. And so it escaped attention. This geometrical tradition was then “overcome” much later after long millennia by the Celts. My personal feeling from the drawing is that it is a “message”, the representation of an event or a record of a complex world of tradition and mythology passed down by word of mouth. The picture is comprised of more than one part. We cannot, unfortunately, read its meaning. It is wrong to think that it is a record of a meaningless act, as I often hear told. Such behaviour was unknown to prehistoric man. We became capable of thinking like this only very recently. And so we have a prehistoric signature in Býčí Skála alongside the hundreds of modern signatures. You certainly won’t find anything else like it in the caves of the Czech Republic.”

is the largest and most highly developed karst area, with the widest range of karst phenomena, in the Czech Republic. Every kind of karst formation with the exception of polje – enclosed karst depressions – can be found here.

The Macocha Abyss

is 138.5 metres deep and is the largest gorge of its kind in the Czech Republic and Central Europe. The upper part (or mouth) of the gorge is 174 metres long and 76 metres wide. The River Punkva, which feeds two lakes, flows along the bottom of the gorge. The upper lake is approximately 13 metres deep and can be seen from above. The lower lake is hidden among the rocks and is not visible from above. It is more than 49 metres deep. Its bottom has yet to be reached.

The first man

known to have descended to the bottom of Macocha was the monk Lazar Schopper from Brno, later Prior Provincial of the Minorite order in Moravia – he achieved the feat in 1723.

The cableway

connecting the Punkva Caves with Macocha is 249 metres long (with a horizontal length of 207 metres) and spans an elevation of 131 metres, making it the steepest cableway in the country. It connects two points – the Punkva Caves (362 metres above sea level) and Macocha (493 metres). The transport speed of the cableway is 2.5 m/s. Its two cabins hold 15 people and the journey time amounts to less than three minutes.

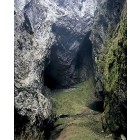

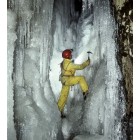

The Rudice Sink

is, at 153 metres, the deepest dry gorge in the Czech Republic. It is located in the Rudice Sink – Býčí Skála cave system. The gorge was discovered by speleologists climbing the U Kašny stack right above the active riverbed of the Jedovnice Stream. Ascents to a height of 146 metres proved possible in time. Following accurate measurement and the digging out of a seven-metre plug, a new entrance was built on the surface which can be found on the edge of the forest to the south of Rudice.

The Amateur Caves

in the Moravian Karst is the longest cave system in the Czech Republic. The areas explored to date amount to a length of almost 35 km.

The first automobile

in the country was made in Adamov in 1888–1889 just three years after Daimler’s first automobile with a combustion engine. Only one “Marcus” automobile with a four-stroke petrol engine was, unfortunately, made. Today, it is the pride and joy of the Technical Museum in Vienna.

Mysterious skulls

were discovered in 1991 in the charnel house beneath the church in Křtiny. Among the skeletal remains of around a thousand people, twelve skulls were discovered that were painted with black laurel wreaths and the Old Canaanite letter Tau. These skulls, whose strange ornamentation evidently dates back to the seventeenth century, may have belonged to distinguished persons – members of the religious order, though a bold theory has emerged according to which they are the skulls of some of the twenty-seven Czech lords executed in 1621. Whatever the truth may be, a number of them can now be seen in the newly restored charnel house in Křtiny.

The oldest cave painting

in the Czech Republic is found in the Býčí Skála (Bull Rock) Cave in the Josefov Valley. The cave is famous primarily for the archaeological discovery of an extraordinarily large burial site from the Early Iron Age and the finding of a statue of a bronze bull. The prehistoric painting is found in an inaccessible part of the cave. Its story is described by archaeologist Mgr. Martin Golec, Ph.D.:

“Býčí Skála has ceilings in the Old Býčí Skála that have been accessible since time immemorial and discoloured by the torches of its visitors. The walls are covered with the signatures of hundreds of inquisitive people who have sought contact here with a mysterious world, an enlightened ideal in the womb of nature or a romantic excursion to the underground. The painting is found in a small recess at the end of the large amphitheatre known as the South Branch in Old Býčí Skála. It does not belong to the Palaeolithic, as we might expect. The site was an extensive winter camp for the Magdalenian hunters for millennia. It is younger, belonging to the Eneolithic, and we can date it back approximately to the middle of the fourth millennium before Christ. How did it escape detection from so many eyes? It is a geometrical structure of hatched triangles and lattices, in the fashion of the times. Nothing realistic. And so it escaped attention. This geometrical tradition was then “overcome” much later after long millennia by the Celts. My personal feeling from the drawing is that it is a “message”, the representation of an event or a record of a complex world of tradition and mythology passed down by word of mouth. The picture is comprised of more than one part. We cannot, unfortunately, read its meaning. It is wrong to think that it is a record of a meaningless act, as I often hear told. Such behaviour was unknown to prehistoric man. We became capable of thinking like this only very recently. And so we have a prehistoric signature in Býčí Skála alongside the hundreds of modern signatures. You certainly won’t find anything else like it in the caves of the Czech Republic.”